4

4

The pop sensuality of Marilyn Minter

Dans ses photos, vidéos et peintures, cette artiste sans concession applique des effets sophistiqués qui en accentuent le relief. Elle fit scandale dans l’Amérique puritaine des années 90 avec ses œuvres avant-gardistes inspirées de la pornographie.

Par Éric Troncy,

Par Éric Troncy.

Ses premières œuvres, elle les réalisa à 21 ans, en 1969, lorsqu’elle était encore étudiante à l’université de Floride – mais leur présentation initiale ayant été une telle source de malentendus, elle ne les montra à nouveau que trente ans plus tard. Elle est quasiment inconnue en France (où elle n’eut qu’une seule exposition personnelle, en 2001, à la Galerie Thaddaeus Ropac), mais aux États-Unis, elle fut toujours admirée – essentiellement par les artistes, et de toutes générations (la sienne, et celles qui suivirent). Ils ne l’abandonnèrent pas lorsque, en 1990, et au prix une fois encore d’un malentendu, elle fut, selon ses propres termes, “mise au ban du milieu de l’art”.

La rétrospective qui lui fut consacrée en 2015-2016, intitulée Dirty/Pretty et qui circula au Museum of Contemporary Art de Denver, au Contemporary Arts Museum Houston et au Brooklyn Museum de New York, mit fin à tous les malentendus et, qu’on la trouve ou non à son goût, fit la démonstration de la parfaite cohérence et de la solidité de cette œuvre qui se déploie sur une quarantaine d’années. À 71 ans, Marilyn Minter n’a jamais couru après le succès, mais elle l’a finalement rencontré. “Vous ne faites pas de l’art pour avoir du succès. Si vous le faites pour l’amour de l’art, alors tout ira bien car même si vous ne gagnez pas d’argent, au moins vous ferez ce que vous aimez et vous en profiterez à chaque instant.”

Minter est née en 1948 à Shreveport, Louisiane, et a grandi en Floride. Elle prit conscience très tôt de sa capacité à dessiner et mit ce don à profit, à 16 ans, pour fabriquer de faux permis de conduire (elle excellait dans l’exécution au crayon des caractères de machine à écrire) – elle passa quelques jours en prison pour cela. Les photographies de sa mère, qu’elle fit un week-end, dans le cadre de ses études, choquèrent sans qu’elle s’y attende vraiment ses camarades de classe. Elle l’avait photographiée – douze images en noir et blanc (Coral Ridge Towers, 1969) –, dans son ordinaire oisif, c’est-à-dire essentiellement allongée dans son lit et fumant des clopes, ou se teignant les sourcils, toujours vêtue d’une nuisette. “Elle était très glamour, toujours perchée”, explique Minter qui, habituée à ce spectacle, n’avait pas anticipé les réactions des autres étudiants qui y virent un portrait maternel accablant. Elle rangea les litigieuses images, et ne les montra plus.

Lorsqu’elle s’installa à New York dans les années 70, Minter s’attacha à produire des peintures relevant de ce qu’elle nomme, avec une bonne dose d’ironie, un “photoréalisme chiant” (“boring photorealism”) qui, selon elle, prenait acte de la vivacité du photoréalisme des années 60 et de la nouvelle tendance conceptuelle de l’art qui faisait florès dans les galeries newyorkaises. Elles représentent deux photos en noir et blanc traînant sur un sol en linoléum gris (Photos on the Floor, 1976), une feuille de papier aluminium froissé sur le même linoléum (Aluminum Foil, 1976), le coin d’une planche de contreplaqué, une coquille d’œuf et une vieille éponge dans le bac d’un évier en Inox, bref, des sujets sans éclat et d’une banalité absolue. Elle les expose en laissant la toile libre, sans cadre et simplement agrafée sur le mur. La collaboration qu’elle mène dans les années 80 avec l’artiste allemand Christof Kohlhöfer (qui travailla aussi pour Sigmar Polke) la familiarise avec les techniques utilisées par Polke – en l’occurrence la projection d’une image réglée de telle sorte que les points qui la constituent soient exagérément grossis. Des œuvres, en somme, qui disent l’ambition d’explorer les formes de l’avantgarde de son époque, mais loin, encore, de l’univers qu’elle mettra en place à la fin de la décennie.

“Vous ne faites pas de l’art pour avoir du succès. Si vous le faites pour l’amour de l’art, alors tout ira bien car même si vous ne gagnez pas d’argent, au moins vous ferez ce que vous aimez et vous en profiterez à chaque instant.”

Les année 90 formèrent un tournant décisif pour Marilyn Minter, qui se demanda quel sujet les femmes artistes n’avaient encore jamais abordé. La réponse fut sans appel : la pornographie hard. Dès la fin des années 80, Minter peint à partir d’images pornographiques (Porn Grid, 1989) et aborde son exposition à la galerie Simon Watson, bien décidée à ne pas respecter grand-chose, à commencer par l’emploi des traditionnels encarts promotionnels pour annoncer la manifestation dans les magazines spécialisés, auxquels elle préfère trente secondes de film publicitaire en plein milieu du Late Show de David Letterman, pour une somme de 1 800 dollars.

Elle réalise une centaine de tableaux, inspirés par des photographies de nourriture : mains aux ongles vernis de rouge vif occupées à séparer le blanc du jaune d’un œuf ou à ouvrir des écrevisses, traitées dans une veine pop mâtinée de coulures et révélant une trame grossière. Ce sont quelque cent tableaux qu’elle filme et assemble en un spot publicitaire destiné à la télévision – une première, assurément, et qui apparaît, rétrospectivement, comme un commentaire violent du devenir entertainment de l’art. “Si vous ne saviez pas de quoi il s’agissait, vous n’auriez jamais pu le savoir”, explique Minter, commentant le caractère éminemment surréaliste de ce film publicitaire à cet endroit précis. Les féministes y verront autre chose, de bien moins supportable à leurs yeux : fallait-il bien que Minter montrât des femmes occupées à faire la cuisine, transformées en objets sexuels, et tout cela sans que les œuvres laissent transparaître la moindre distance critique vis-à-vis de la violence du sujet ?

C’est, justement, la marque de fabrique de Minter : on cherchera en vain dans ses œuvres toute forme de commentaire. D’ailleurs, une époque qui fit des œuvres un permanent bavardage, et finalement un vecteur de bonne conscience, avait peu de chances de s’accommoder des Food Porn de Minter. En effet, l’Amérique, alors sous la domination du politically correct, supporta mal ces œuvres. “Je me suis sentie mise au ban du milieu de l’art”, déclare l’artiste, se souvenant que le galeriste ferma l’exposition une semaine avant son terme, lassé des controverses. Elle se souvient aussi du soutien indéfectible de ses amis artistes : Cady Noland, Larry Clark, Jack Pierson, Jessica Stockholder, Laurie Simmons, Mary Heilmann… “Des artistes reconnus. Mais il y eut une époque où ils ne pouvaient même pas me défendre car cela les mettait eux-mêmes trop en péril.”

Fort logiquement, la controverse n’eut aucun effet de censure sur Marilyn Minter, qui continua de plus belle. L’année qui suivit les Food Porn, Jeff Koons présenta ses premières œuvres montrant ses ébats sexuels avec la Cicciolina… Minter ne vécut pas cela comme une traversée du désert et continua à faire les œuvres qui lui plaisaient. “Et en 1995, lorsque je présentai les photos de ma mère, on me rouvrit la porte à nouveau. Je pense que le milieu culturel accorde du crédit aux artistes issus d’un environnement dysfonctionnel. D’une certaine façon, cela légitime leur travail”, expliquait-elle à Glenn O’Brien il y a quelques années. Depuis lors, elle a structuré une œuvre en tout point fidèle à ses aspirations originelles, qui se décline en photographies (en petit nombre et jamais retouchées), vidéos (essentiellement pour des occasions commerciales) et peintures aux couleurs criardes, inspirées par la photographie de mode et la photographie pornographique.

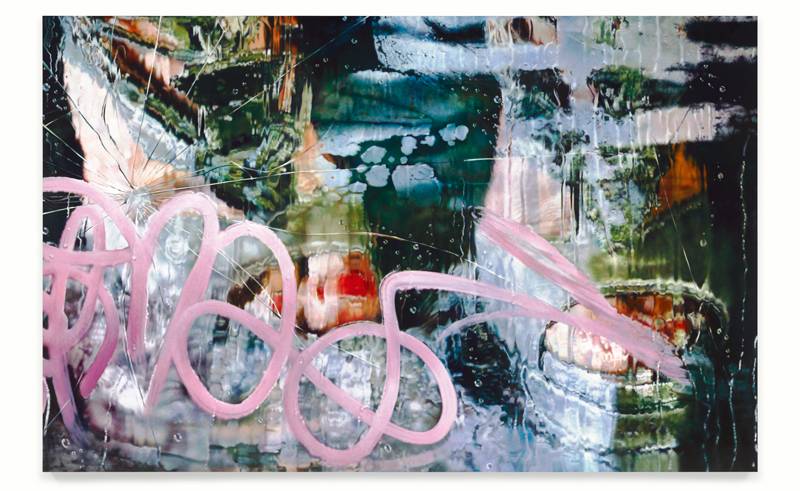

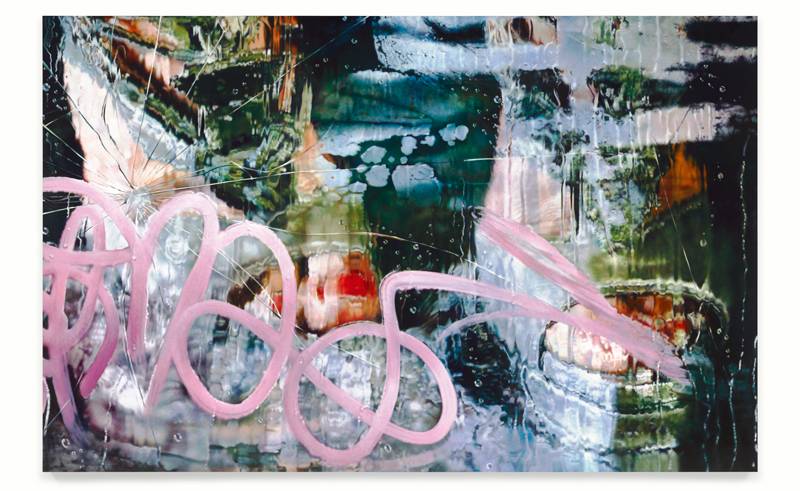

Elle peint sur métal, se sert de ses doigts plutôt que de pinceaux, et conçoit ses tableaux avec la patience qu’il faut pour appliquer des dizaines de couches de peinture sur la toile, cherchant toujours plus de profondeur. “Il y a une profondeur, une richesse dans la peinture que vous ne pouvez jamais obtenir dans une photo.” À la différence de ses images, les peintures sont composées de multiples clichés que Minter produit elle-même et assemble, s’en donnant à cœur joie avec Photoshop. Depuis 2009, ses images semblent réalisées derrière une plaque de verre qui leur donne à la fois une proximité et une distance : comme une affiche publicitaire à un arrêt de bus sur laquelle on aurait ajouté des tags, ou comme la vitre d’une douche sur laquelle la condensation forme autant de petites perles d’eau. Les sujets (pas uniquement des femmes, elle insiste) n’y sont pas montrés sous un jour flatteur. “Je ne pense pas qu’il soit vraiment intéressant de réaliser un joli visage de plus, ou une jolie image publicitaire de plus. Je veux simplement montrer ce que cela signifie de vivre dans un monde où vous êtes constamment bombardé d’images et où elles ne semblent plus précieuses.”

She made her first notorious work at 21, in 1969, when she was still an art student at the University of Florida, but it was so misunderstood that she didn’t show it again for another 30 years. She’s barely known in France, where she’s only had one solo show (at Galerie Thaddaeus Ropac in 2001), but in the U.S. she’s always been admired, essentially by artists – of all generations, her own and those that followed. They didn’t abandon her when, in 1990, she was “thrown out of the art world,” as she puts it, due to further incomprehension of her work.

Her 2015 retrospective, Dirty/Pretty, which was shown at the Denver Museum of Contemporary Art, the Houston Contemporary Arts Museum and at New York’s Brooklyn Museum, put an end to all the misunderstandings, and, whether or not it By Éric Troncy is to one’s taste, amply demonstrated the perfect coherence and solidity of an oeuvre spanning 40 years. Now 71, Marilyn Minter has never sought success, but it has finally found her. “You don’t make art to be successful. If you make art for the love of it, then you’ll be fine, because even if you don’t earn any money, at least you’ll be making what you like. You’ll enjoy doing it.”

Minter was born in 1948 in Shreveport, Louisiana, and grew up in Florida. She exhibited a precocious talent for drawing and put her gift to profitable use when, at 16, she started faking driving licences – she was a dab hand at reproducing typescript with a pencil –, which earned her a few days in jail. The photos she made of her mother one weekend, while at art school in Gainesville, shocked her classmates, a reaction she didn’t expect. The 12 black-andwhite images (Coral Ridge Towers, 1969) showed their subject in her everyday idleness, lying in bed smoking, or dyeing her eyebrows, permanently dressed in a nightgown. “My mother was a drug addict. She never really left the house and almost always wore a nightgown … She was a beautiful woman at one time, still very concerned about her looks, but a little off … She was never quite right in terms of glamour,” explains Minter, who hadn’t foreseen that her photos would be interpreted as a damning portrait of their subject. So she filed the offending prints away, and didn’t show them again till 1995.

When she moved to New York in the 70s, Minter started producing work in a register that she ironically describes as “boring photorealism,” which, she says, was a reaction to the vivacity of 60s photorealism and to the conceptual tendencies then proliferating in the Big Apple’s art galleries. Her paintings show subjects such as a pair of black-and-white photos throw down onto a grey lino floor (Photos on the Floor, 1976), a crumpled piece of aluminium foil on the same floor (Aluminum Foil, 1976), the corner of a sheet of plywood, an eggshell and an old sponge in a stainless-steel sink, and other such unglamorous, unheroic banalities. She exhibited them without frames or chassis, simply stapled to the wall. In the 80s she teamed up with German artist Christof Kohlhöfer, who had worked with Sigmar Polke, and thus became familiar with some of Polke’s techniques, like the projection of an image so that it appears exaggeratedly enlarged. An oeuvre, in other words, that showed her ambition to explore the avant-garde art forms of her time, but which was still a million miles from the universe she would go on to develop at the end of the decade.

“Did Minter have to show women doing the cooking and transformed into sex objects without the least critical distance with respect to the violence of the subject?”

The late 80s represented a major turning point for Minter, who looked around to see which subjects women artists hadn’t yet tackled, and came up with an irrevocable answer: hard porn. So began her series of paintings drawn from pornographic imagery, such as Porn Grid (1989). Determined to ignore conventions, including the traditional exhibition adverts in the art press, she chose to promote a 1990 show she was preparing at the Simon Watson gallery with a 30-second video that was aired on primetime TV, in the ad breaks of broadcasts such as David Letterman’s Late Show, at $1,800 a slot.

100 FOOD PORN, as it’s titled, showcases pictures inspired by food photography: red-nailed fingers separating eggs or shelling shrimp, all realized in a Pop manner with abundant paint drips and half-toning dots that reveal their printed-matter origins. The video, which must surely have been a first, seems with hindsight to be a violent commentary on art’s future as entertainment. “If you didn’t know what it was about, you’d probably not have guessed,” explains Minter with respect to the entirely Surrealist effect of that particular film being shown in that particular context. Feminists saw in it something other, which was a lot less acceptable to their eyes: did Minter have to show women doing the cooking and transformed into sex objects without the least critical distance with respect to the violence of the subject?

But that is precisely Minter’s trademark: nowhere is there any form of commentary in her work, a problem in a period when art was all about the politically correct. And so, once again, America reacted unfavourably to her work. “I felt like I got thrown out of the art world,” she declares as she recalls how her gallerist, fed up with the controversy, closed the Food Porn show a week early. She also remembers the unfailing support of her artist friends: Cady Noland, Larry Clark, Jack Pierson, Jessica Stockholder, Laurie Simmons and Mary Heilmann, among others. “Well-known artists. But there was a time when they couldn’t even defend me because it was too dangerous for them,” she remembers.

“I don’t really think it’s interesting to make another pretty face or another good-looking ad. I just want to make a picture of what it’s like to live in a world where you’re constantly bombarded with images and they’re not necessarily precious anymore.”

The controversy of course had no calming effect on Minter, who, true to form, pushed things even further. The year after her Food Porn series, Jeff Koons would unveil his first couplings with La Cicciolina… But Minter just carried on doing what she liked. “And in 1995, when I showed the pictures of my mother, I got let back in. I think that the culture trusts artists who come from dysfunction. Somehow this legitimizes the work,” she explained to Glenn O’Brien a few years ago. Since then she has been producing a body of work that is in every way faithful to her original intentions, and comprises photographs (in small quantities and never retouched), videos (essentially for commercial events) and garish paintings inspired by fashion and porn photography.

She mostly works on metal, uses her fingers rather than brushes, and musters all the patience necessary to apply layer after layer of paint. “There is a depth, a richness in a painting that you could never get in a photo,” she explains. Unlike her photography, her paintings are drawn from countless shots that she takes herself and then assembles in Photoshop. As of 2009, her images seem as though realized behind a sheet of glass, giving them a feeling of both proximity and of distance, like a bus-stop advert that’s been graffitied, or a wet shower screen covered with droplets of water. Her subjects – not only women, she insists – are not exactly shown in a flattering light. “I don’t really think it’s interesting to make another pretty face or another good-looking ad. I just want to make a picture of what it’s like to live in a world where you’re constantly bombarded with images and they’re not necessarily precious anymore.”