2

2

Meet artist Christopher Wool, the master who creates tension between painting and erasing, gesture and removal

À l’occasion de sa récente exposition chez Xavier Hufkens, à Bruxelles, Christopher Wool dévoilait de nouvelles et rares peintures, photographies et sculptures. Dans un entretien exclusif, l’artiste parmi les plus importants de son époque revient sur son parcours et sur une pratique qui s’est toujours caractérisée par la multiplicité des médiums et des techniques (spray, sérigraphie, reproduction numérique…), additionnant, superposant, manipulant ou effaçant les images.

Par Nicolas Trembley,

By Nicolas Trembley.

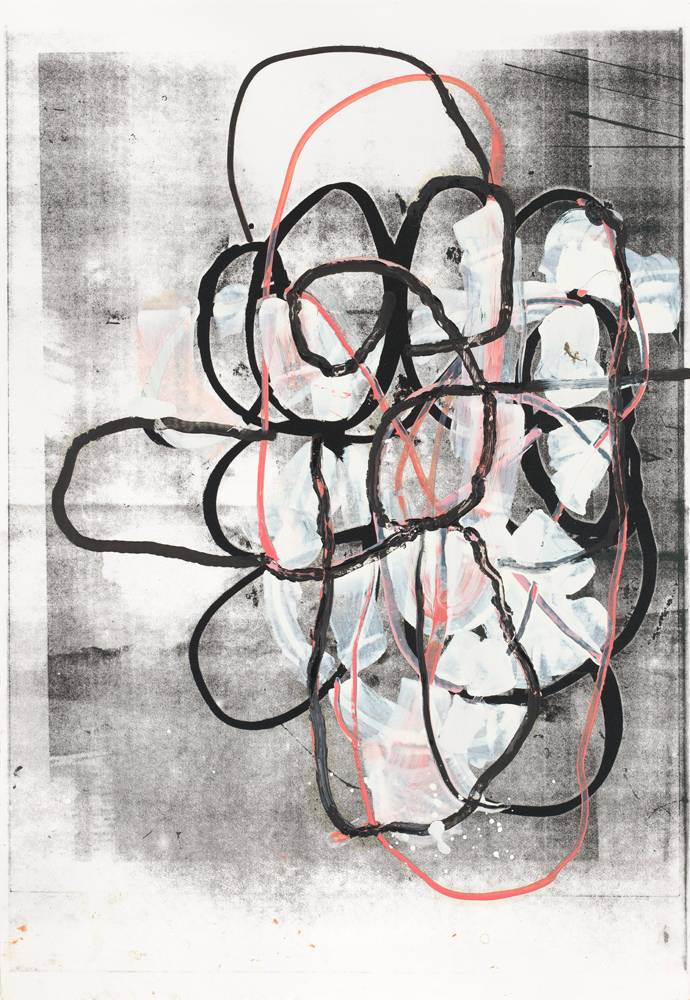

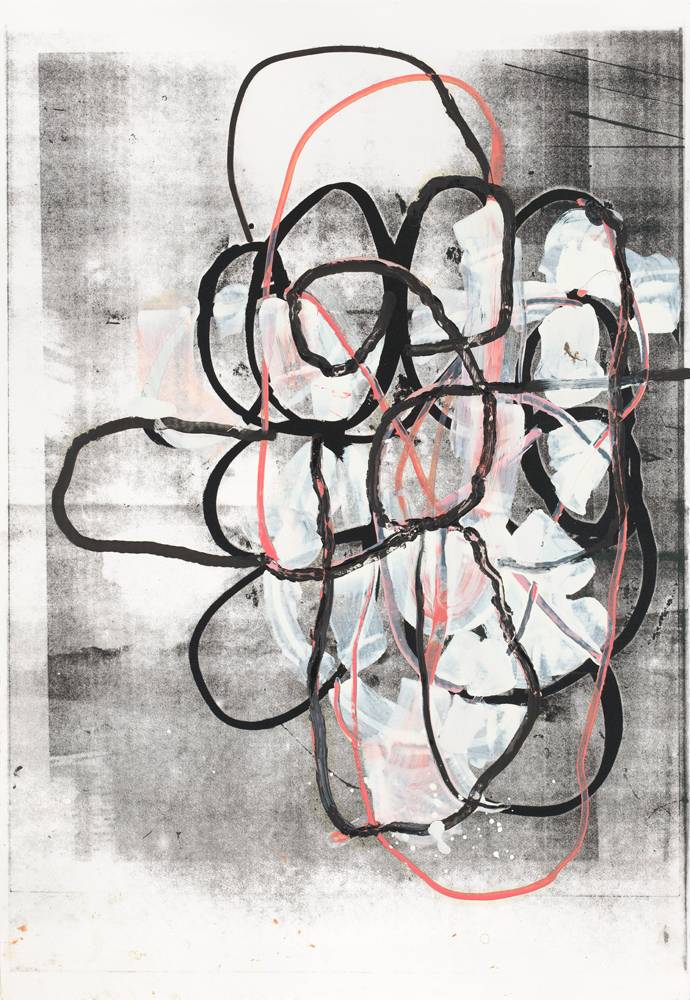

En juin dernier, le belge Xavie Hufkens inaugurait sa nouvelle galerie avec Christopher Wool (1955, vit à New York et Marfa, au Texas), une exposition conçue avec la curatrice Anne Pontegnie, collaboratrice de longue date de l’artiste américain. On pouvait y découvrir l’étendue de sa pratique, à travers de rares nouvelles peintures qui faisaient écho à des œuvres sur papier, des photographies et de nouvelles sculptures en métal. Wool est l’un des artistes les plus pertinents concernant les questions de production de différents régimes d’images. Il les additionne, les fait se soustraire les unes aux autres, les manipule, les superpose ou simplement les efface. L’image n’est plus simplement image mais un processus qui pousse à la réflexion sur la mémoire, la disparition et le processus créatif au sens élémentaire. Nous l’avons rencontré lors de l’accrochage de son exposition à Bruxelles.

Nicolas Trembley : Le début des années 80 a vu apparaître de nombreux artistes figuratifs, après l’art minimaliste et l’art conceptuel. Mais vous ne vous inscriviez pas dans ce registre.

Christopher Wool : Non, pour moi, la peinture avait encore des choses à dire. La fin des années 70 avait sans doute été en demi-teinte dans le monde de l’art, mais tout à coup, les artistes de la Pictures Generation se sont mis à montrer leur travail et il s’est passé beaucoup de choses – la première exposition de Julian Schnabel, par exemple. Le dialogue artistique était très nourri.

Êtes-vous plutôt issu de la Pictures Generation, qui intègre la photographie et l’image filmée, ou d’un environnement plus pictural ? Parce qu’on parle avant tout de votre peinture…

Je viens de la Studio School de New York, donc d’un contexte plus traditionnel, axé sur la peinture. Beaucoup d’artistes de la Pictures Generation ont rejeté ce medium et je crois que je n’ai pas réagi de la même façon parce que j’étais un peu plus jeune – j’avais un an ou deux de moins qu’eux. Le temps que cette idée de rejet de la peinture s’installe, ce renoncement m’était déjà devenu inutile.

Vous travaillez sur différents mediums. Vous sentez-vous plus à l’aise avec l’un d’eux en particulier, ou l’enjeu tient-il d’abord à leur combinaison?

Je reste peintre avant tout. Richard Prince disait de son recours à la photographie “qu’il la pratiquait sans permis”. Je trouve que c’est une très bonne définition, parce que je n’aborde pas la photographie comme le ferait un photographe. C’est sans doute la même chose pour la sculpture : il faut que je m’habitue à la troisième dimension, c’est nouveau pour moi.

Comment est-ce arrivé ?

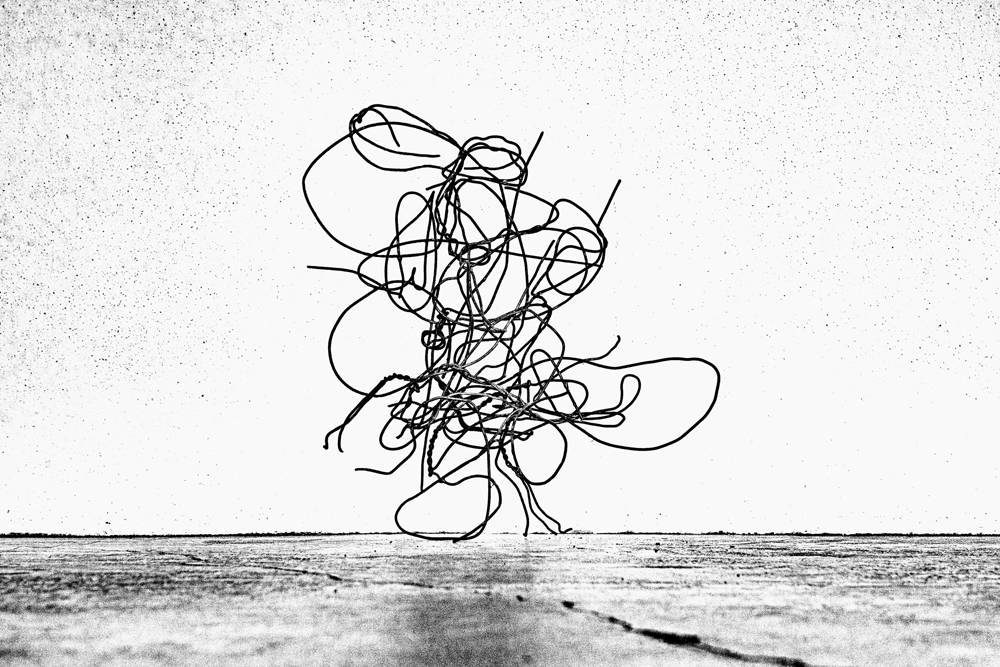

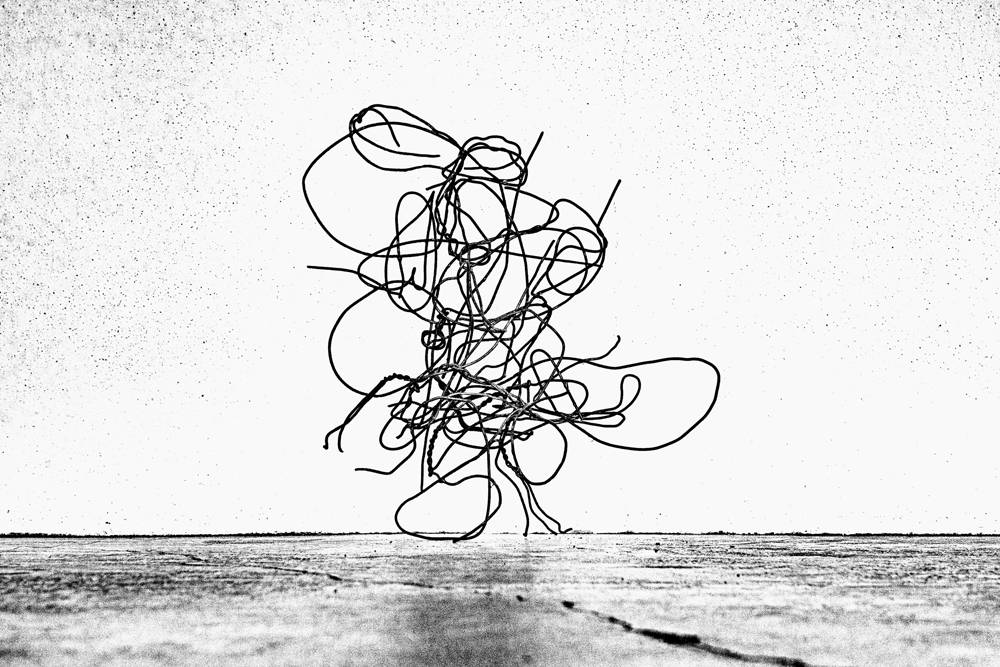

Assez simplement. Lorsque nous avons acheté une maison à Marfa, au Texas, il m’a paru tout naturel de réfléchir à des choses plus imposantes, en 3D : il y a tellement d’espace là-bas. Je sortais avec mon appareil photo pour relever des choses drôles, intéressantes, amusantes, qui avaient une dimension sculpturale. Ce pouvait être un élément placé de manière décalée dans un jardin ou des objets industriels. J’en ai fait un livre de photos, Westtexaspsychosculpture. Le concept de Psychosculpture est un emprunt aux Psychobuildings de l’artiste allemand Martin Kippenberger. Je réfléchissais donc à la sculpture, sans avoir de projet précis ne tête. Puis dans le ranch voisin, j’ai trouvé de grandes quantités de fil de fer pour les clôtures. J’en ai ramassé, trouvant que ce matériau avait une belle ligne, assez similaire à celles que je trace en dessinant. J’ai fini par réussir à faire tenir le tout debout et ces fils de fer sont devenus des sculptures tridimensionnelles. J’ai mis quelques années ensuite à en faire des œuvres d’art.

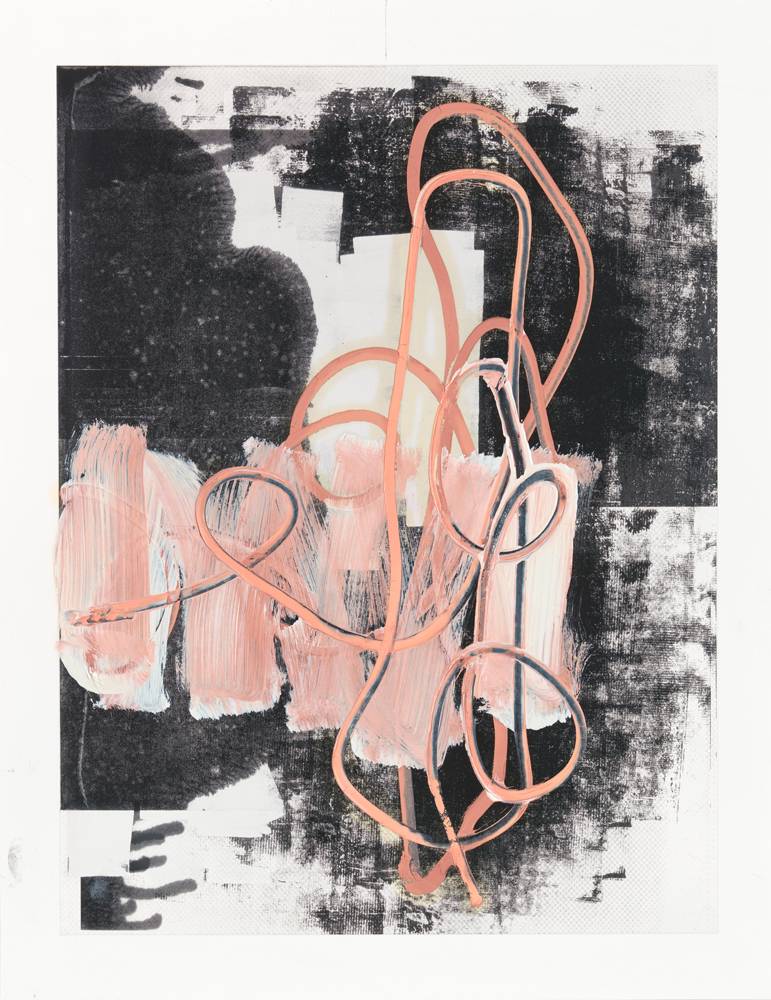

“J’ai laissé toutes les soudures apparentes pour qu’on voit le processus d’assemblage”, dites-vous. Cela me rappelle le processus de la sérigraphie, où l’on voit le travail manuel, mais qui est accompli par un geste mécanisé.

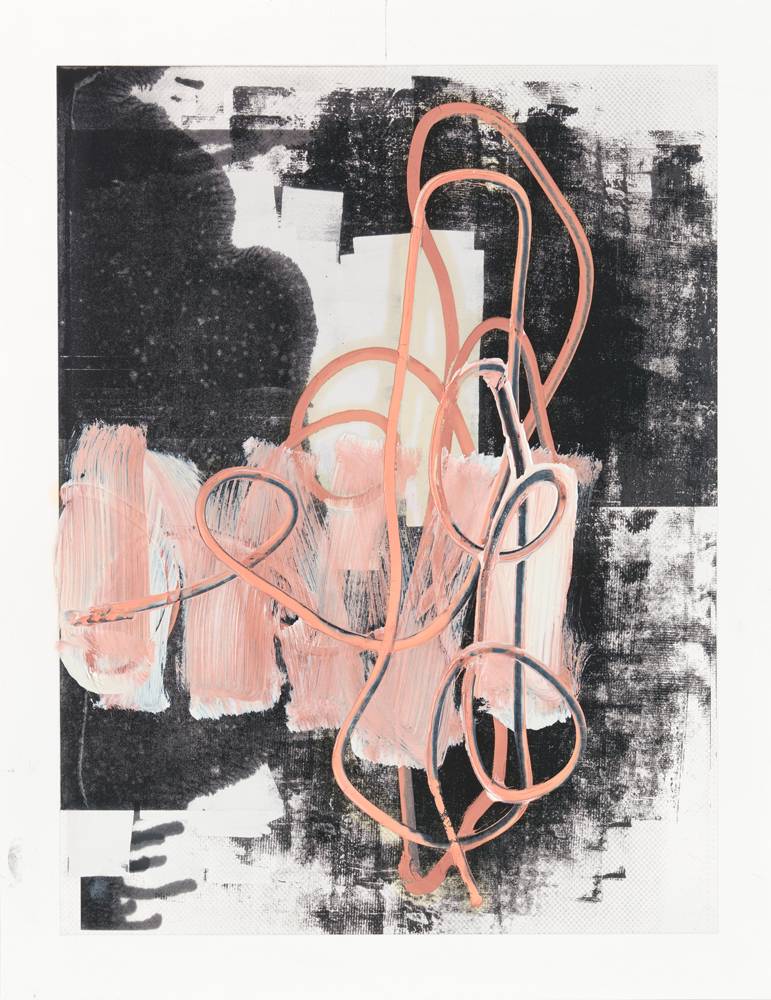

Je réalise moi-même mes sérigraphies et cela peut sembler être un processus mécanique. Pourtant, il y a des manières très expressives de travailler le tissu-écran, il suffit de penser à Warhol. J’exerce le même type de contrôle lorsque je réalise la toile – la densité, la focalisation… Pour moi, cela se rapproche d’un processus observable, comme une goutte tombée dans la peinture : on peut la voir, on sent que c’est fait à la main. Avec la sérigraphie, on voit que ce n’est pas complètement mécanisé, mais imprimé comme pour une impression professionnelle. C’est ce qui donne au public un point d’entrée dans la toile.

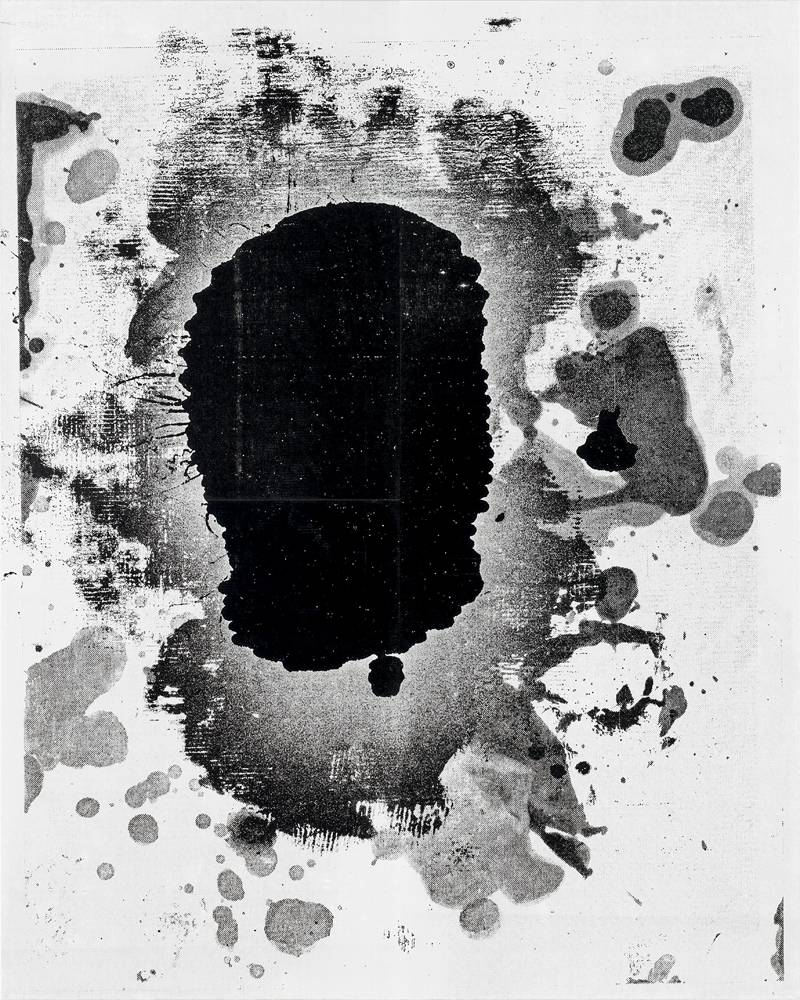

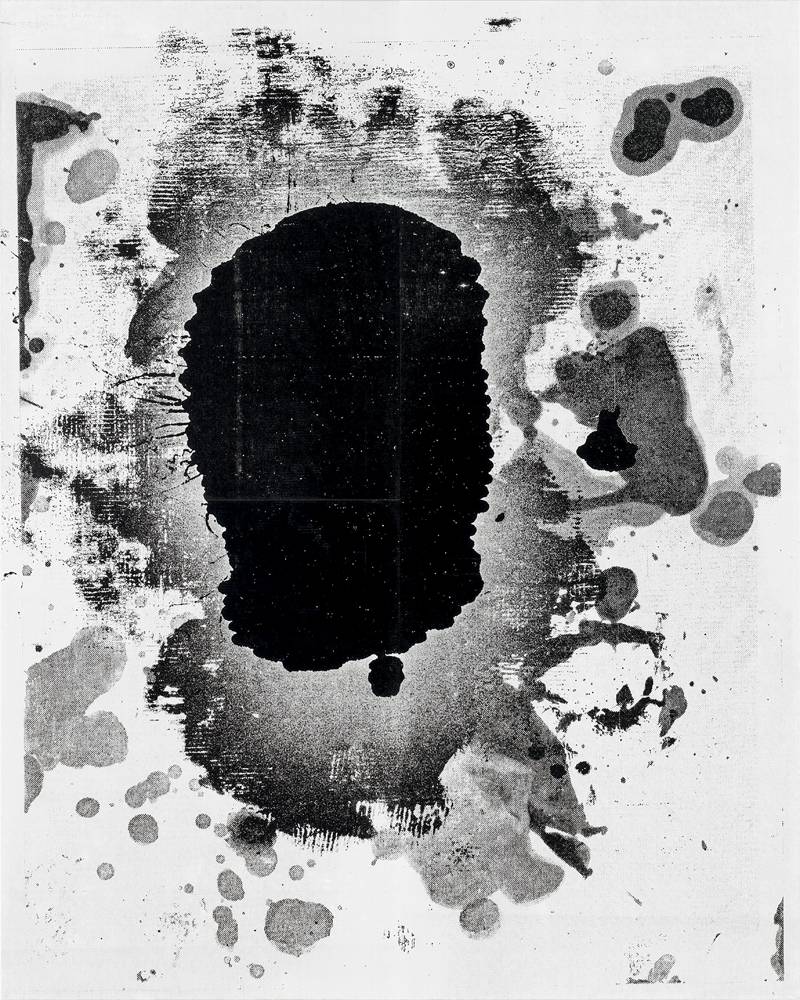

Vous travaillez sur certaines pièces depuis plusieurs années déjà. Vous y êtes revenu, en employant différentes techniques, vous les avez scannées, peintes, photographiées. À quel moment considérez-vous que l’œuvre est terminée ?

Je me fie à mon expérience et à mon instinct. Je n’arrête jamais de chercher du nouveau, du différent. Tout le défi est de savoir comment terminer la toile peinte et ce qu’elle va raconter. Avant, je travaillais dans mon atelier avec des Polaroid, je prenais une photo pour voir où j’en étais. J’ai conservé toutes ces photos dans une boîte pendant une dizaine d’années. C’était intéressant de revoir toutes ces toiles par-dessus lesquelles j’avais peint et toutes celles que je n’avais pas considérées comme des “peintures achevées” mais qui auraient probablement dû l’être. Je dirais que, par opposition à la vision idéale du modernisme, il n’y a pas une seule peinture parfaite, à laquelle on aspirerait. Beaucoup de choses peuvent se produire, toutes potentiellement intéressantes. C’est ça qui est excitant !

Nicolas Trembley: After minimalism and conceptualism, the early 1980s saw the arrival of figurative artists. But you weren’t part of this discourse?

Christopher Wool: No, I think there was still a painting discourse. The late 1970s might have been a slow time in the art world, but when the Pictures Generation started showing – Julian Schnabel’s first show, etc. – there was a lot of dialogue about what was going on.

Would you say you come more from the Pictures Generation, with photography and film, or from paint- ing? People tend to talk more about your paintings…

Yes, I know. I came from the Studio School in New York, a more traditional, painting-oriented background. A lot of Pictures Generation artists rejected painting. I think I was just young enough – I was a year or two younger – that by the time the idea of rejecting painting had settled in, I didn’t need to. I could learn from them, the issues they brought up were important, but it didn’t stop me from painting.

You work with different media. Do you feel more at ease with a particular one or is it about the combination?

No, I think I’m still a painter mostly. Sculpture is new to me. Richard Prince described his use of photography as “practising without a licence”. I think that’s a great description, because I don’t think I come to photography like a pho-tographer would. It’s maybe the same for sculpture: I have to get used to three dimensions, it’s new to me.

What got you started on sculpture?

It was quite simple actually. When we first got a house in Marfa and started spending time there, it just seemed natural to think about larger three-dimensional things, just because there’s so much space. I had my camera and I started noticing funny, interesting, amusing things that were sculptural outside in Marfa – things people put in their yards in a silly way or any kind of industrial object. That became the book Westtexaspsychosculpture. The psychosculpture idea was borrowed from Kippenberger’s book Psychobuildings. So, I was thinking about sculpture without having any specific plans. Then I found all this fencing wire that was left around the ranch next to my house, which I picked up because it had a nice line to it, similar to the line I draw with. It took me a while, but eventually I started making the thing stand up and they became three-dimensional in a simple way. It took a few years before I actually got around to making it art.

“I have left all the welts, so you can see the process of assembling,” you said. To me that’s like silkscreen, where you can see it’s handmade, but it’s a mechanical hand.

I use silkscreen like a brush. It’s just something between my hand and the painting. I do the screening myself and it seems like a very mechanical process. We know from early Warhol that there is an expressive way of working the silk- screen, so I have some control when I’m making the painting – density, focus, all kinds of things. To me, it’s one of those kinds of process that you can see, like a dripping in the painting, you can see it, you can feel that it is handmade. You know that it is not completely mechanical, it’s printed like a professional printer. I think that gives the audience an entrance into the painting. I think visual art has power, that’s the interest to me, and that should communicate to the audience. It’s not a specific message.

You’ve been working on some pieces for several years, coming back to them, using different techniques, scanning them, painting them, photographing them. When do you feel the work is finally finished?

Oh, that’s the million-dollar question! That’s the hard part. I think, with experience, I trust myself, so I can do it a little easier. But I’m always looking for something different and new, and I don’t know what that is until it happens in the painting. So that’s the challenge – to figure out how to finish the painting, and what it’s going to say. I used to work with Polaroids in the studio, and take lots of photos so that I could see where I was. I’ve kept all these photos in a box for ten years now. Looking over them, it was interesting to see all the paintings that got painted over, and all the paintings that weren’t “finished paintings” and probably should have been. I think, as opposed to the high idea of Modernism, there isn’t one particular perfect painting that you’re looking for. All kinds of different things can happen and be interesting. That’s the exciting part!